Article made by Eleonor Nolan,

July 31, 2022.

Synopsis:

Six children were born from the marriage between Richard Grey, a clergyman from a parish in North England, and a wealthy woman. Only two of them survived childhood illnesses: Mary, the eldest, and Agnes, the protagonist of the story. The two girls were deprived from an early age of the fortune that would have corresponded to them by their mother’s ancestry line. It turned out that Mrs. Grey had been disinherited before her wedding. The family of the fiancée considered the future marriage a disgrace, and thus punished the young lady by dispossessing her of the luxuries and comforts to which she had become used to. However, much to her progenitors’ surprise, the bride accepted this decision without any complaint, since material goods mattered little to her compared to uniting herself with the man she loved.

Mary and Agnes grew up full of happiness, thanks to the kindness and tenderness of their parents. Mr. Grey’s income was enough to keep them from going hungry, though not enough to lead a comfortable life. It was not until Mary became a damsel, and Agnes entered puberty, that they had to use their creativity to deal with the debts that the clergyman had gone into after having invested his capital in a mercantile business that brought the financial ruin of the family. Mrs. Grey took over of the household, firing servants, selling the horses and carriage, and mending their clothes over and over again since they couldn’t afford new dresses. Mary began to sell her watercolors, as she was talented at painting. Meanwhile, Agnes decided to be a governess despite the jocular comments of father, mother and sister. Being the youngest of the family, she had always been treated too indulgently. However, Agnes managed to overcome her family’s disapproval, and got a position as a teacher in Wellwood House, the mansion of the Bloomfield.

Agnes remained in said residence for no more than twelve months. At the end of this period she returned to the Rectory; that is, her family’s home. Although she had managed to save a few pounds, she felt humiliated by Mr. and Mrs. Bloomfield’s treatment, and disillusioned by her little progress in the tasks of educating. Nevertheless, after a reasonable time, Agnes tried to get another position. To do this, she posted an ad in the local newspaper detailing her skills and knowledge on various subjects. Mrs. Murray, Horton Lodge’s mistress, a mansion some fifty miles away, responded to the notice. After a brief exchange of letters between the women, Agnes engaged as governess to four children. She spend three years in Horton Lodge; the last of which changed her fate.

Characters

Bloomfield family

▪ Mrs. Bloomfield:

She was a cold-hearted woman, unsympathetic in her conduct-towards the servants, her husband or her own children. The firstborn of the family, however, was treated very differently by Mrs. Bloomfield as she behaved with him like an affectionate and indulgent mother. It should also be mentioned that Mrs. Bloomfield cared little about the inappropriate behavior of others, such as their coarse and vulgar manners, if such conduct did not damage her reputation as a distinguished and self-restrained woman.

▪ Mr. Bloomfield:

He was a man of ruthless, and irritable character. Among some of the many things that drove him crazy were the lack of punctuality; the sloppiness of the clothing of his children; the disorder of dirty rooms and halls of the house; and the constant carelessness of the servants when preparing dishes without taking into consideration his pretentious culinary tastes. He also had the peculiarity of indulging in the pleasure of drinking gin daily and in excess, which made his temperament even more irascible.

What is the matter with the mutton, my dear?’ asked his mate.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 17 and 18).

‘It is quite overdone. Don’t you taste, Mrs. Bloomfield, that all the goodness is roasted out of it? And can’t you see that all that nice, red gravy is completely dried away?’

‘Well, I think the beef will suit you.’

The beef was set before him, and he began to carve, but with the most rueful expressions of discontent.

‘What is the matter with the beef, Mr. Bloomfield? I’m sure I thought it was very nice.’

‘And so it was very nice. A nicer joint could not be; but it is quite spoiled,’ replied he, dolefully.

‘How so?’

‘How so! Why, don’t you see how it is cut? Dear—dear! it is quite shocking!’

‘They must have cut it wrong in the kitchen, then, for I’m sure I carved it quite properly here, yesterday.’

‘No doubt they cut it wrong in the kitchen—the savages! Dear—dear! Did ever any one see such a fine piece of beef so completely ruined? But remember that, in future, when a decent dish leaves this table, they shall not touch it in the kitchen. Remember that, Mrs. Bloomfield!’

▪ Tom Bloomfield:

The eldest of the four children of the Bloomfield marriage. When Miss Grey took up residence at Wellwood House to take charge of his education, the boy was seven years old. Spoiled by his mother, his uncle, and his grandmother, he behaved as a petty tyrant forcing his sisters to submit to his will. He was also a ruthless creature with animals. The boy’s favorite pastime consisted of torturing birds by ripping off their wings, legs, and twisting their necks until they were decapitated. In addition to these personality traits, the heir to the Bloomfield’s fortune was not deprived of causing several inconveniences to Miss Grey as he frequently suffered fits of rage in class. During these episodes, Tom twisted his body into wild contortions as he punched his governess. However, Miss Grey always managed to appease his spirits by imposing her authority on the boy’s physical strength.

‘Now you must put on your bonnet and shawl,’ said the little hero, ‘and I’ll show you my garden.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 14).

‘And mine,’ said Mary Ann.

Tom lifted his fist with a menacing gesture; she uttered a loud, shrill scream, ran to the other side of me, and made a face at him.

‘Surely, Tom, you would not strike your sister! I hope I shall never see you do that.’

‘You will sometimes: I’m obliged to do it now and then to keep her in order.’

▪ Mary Ann Bloomfield:

A year younger than his brother, she was six years old when she received her first reading and writing lessons. She was already a sloth-prone creature at the time. Such was the case, that her greatest delight was to lie on the floor of the classroom, ignoring the presence of her governess, until it was time for lunch, or tea. Miss Grey often had to lift her with one arm, as if she was a dead weight, and with the other put in front of her eyes the book that she had to read aloud. Like Tom, the girl had also inherited his father’s irritable nature as she suffered outbursts of anger that manifested as wild screams at her teacher’s attempts to discipline her. In contrast to this aspect of her personality, Mary Ann was, as well, a presumptuous childe especially susceptible to flattery.

▪ Fanny Bloomfield:

She was a restless and capricious four-year-old girl. She was no more civilized than her older brother and sister, as she exhibited just as inappropriate behavior as they did. However, Fanny’s demeanor was peculiar unpleasant for those who were in charge of her care. She had a nasty habit of spitting in the face of anyone who did not comply with her demands. She also entertained herself by doing the same with those objects that were not her property, which caused the displeasure of their owners. Fanny had also the same angry temper as almost every member of her family, and she showed it by making horrible guttural sounds when she was enraged. Still, her parents thought she was a sweet and quiet child, which is why they believed that her hostile behavior during her lessons’ hours was due to improper treatment by her governess.

▪ Old Mrs Bloomfield:

Mother of the owner of Wellwood House. Even though she was a cheerful and loquacious lady, she was also an indiscreet and hypocritical woman. She used to express her thoughts out loud with exaggerated gestures and emphatic expressions. She hated her daughter-in-law as much as the latter hated her. However, old Mrs. Bloomfield never made a clear allusion to her animosity toward the aforementioned.

One of her greatest delights was causing discord among the inhabitants of the mansion. To do this, she used the influence she exerted over her son, since he usually listened to what she had to say; usually it was gossip, and covert criticism of the servants. To conclude, the old lady loved receiving compliments. Her will could be twisted in favor of those who knew how to win her sympathy.

At one time, I, merely in common civility, asked after her cough; immediately her long visage relaxed into a smile, and she favoured me with a particular history of that and her other infirmities, followed by an account of her pious resignation, delivered in the usual emphatic, declamatory style, which no writing can portray.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 28).

‘But there’s one remedy for all, my dear, and that’s resignation’ (a toss of the head), ‘resignation to the will of heaven!’ (an uplifting of the hands and eyes). ‘It has always supported me through all my trials, and always will do’ (a succession of nods). ‘But then, it isn’t everybody that can say that’ (a shake of the head); ‘but I’m one of the pious ones, Miss Grey!’ (a very significant nod and toss). ‘And, thank heaven, I always was’ (another nod), ‘and I glory in it!’ (an emphatic clasping of the hands and shaking of the head).

▪ Mr. Robson:

Young Mrs. Bloomfield’s brother, that is, uncle of her four children. He feign to be a gentleman, carrying himself with an arrogant air and flaunting a slim and stylized figure that he had managed to noticeably reduce from the waist up thanks to the use of a corset. His manner, however, were invariably undiplomatic. One of his favorite hobbies was hunting on his brother-in-law’s lands. On these occasions, he used to go with the children looking for bird nests to amuse himself by mistreating the chicks. Tom and Mary Ann were, respectively, his favorite nephew and niece. He encouraged the first one to behave as brutally as possible, and induced him to drink alcohol persuading him that such a habit would make him a more virile man. Regarding the girl, he constantly flattered her with comments a about the beauty of her face, and her lovely smile.

‘Well, you are a good ’un!’ exclaimed he, at length, taking up his weapon and proceeding towards the house. ‘Damme, but the lad has some spunk in him, too. Curse me, if ever I saw a nobler little scoundrel than that. He’s beyond petticoat government already: by God! he defies mother, granny, governess, and all! Ha, ha, ha! Never mind, Tom, I’ll get you another brood to-morrow.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 33).

Murray family

▪ MRS. Murray:

She was a forty-year-old lady whose face did not require makeup to enhance the beauty of her features. As a typical upper-class woman, her amusements consisted of organizing balls for the aristocratic families residing in the area, or attending those offered by her friendships. As the elegant and flirtatious noblewoman that she was, her wardrobe certainly showed her exquisite taste as she was aware of the latest fashion trends. Regarding her family life, she was a loving and caring mother, expressing sincere concern for the well-being of her children. Her criteria, however, as to how to procure them happiness, was based on the belief that the possession of wealth and a high social rank would be enough for it. To conclude, and to respect to housekeeping, it can be said that her treatment of the domestic staff was cordial but not as kind as a master could be with the servants while maintaining social formalities.

‘Miss Grey,’ she began,—‘dear! how can you sit at your drawing such a day as this?’ (She thought I was doing it for my own pleasure.)‘I wonder you don’t put on your bonnet and go out with the young ladies (…) If you would try to amuse Miss Matilda yourself a little more, I think she would not be driven to seek amusement in the companionship of dogs and horses and grooms, so much as she is; and if you would be a little more cheerful and conversable with Miss Murray, she would not so often go wandering in the fields with a book in her hand. However, I don’t want to vex you,’ added she, seeing, I suppose, that my cheeks burned and my hand trembled with some unamiable emotion. ‘Do, pray, try not to be so touchy— there’s no speaking to you else.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 80).

▪ Mr. Murray:

As an expert horseman and skilled hunter, he devoted most of his time to these pastimes, so he was rarely seen in the family residence. In carrying out these activities, Mr. Murray often addressed his dependents with impolite language, often cursing. As his sons were too young to share with them the pleasure of hunting, he instilled in Matilda, his favorite daughter, his same habits, resulting in the girl behaving with the mannerisms and attitudes of a man instead of those of a refined young lady. Despite the long hours he spent in the fields, he used to join his wife and children for dinner as he enjoyed the a copious meal and wine tasting.

▪ Rosalie Murray:

She was the firstborn of the family. At sixteen, she already had well-developed muscles. Her silhouette was slender and stylized. Her skin was a bewitching whiteness; her eyes, a very light blue tone; and her hair, brown with blonde highlights. As for her personality, she was somewhat frivolous. Her main interest was to arouse the admiration of men, and to have the greatest number of suitors surrendered at her feet. She had a talent for languages, music, dance and drawing (although in this last discipline she did not try more than necessary). She was not interested in other subjects of study if it was not possible to show off with them through a simple and banal conversation.

‘Oh, but you know I never agree with you on those points. Now, wait a bit, and I’ll tell you my principal admirers—those who made themselves very conspicuous that night and after: for I’ve been to two parties since. Unfortunately the two noblemen, Lord G—and Lord F—, were married, or I might have condescended to be particularly gracious to them; as it was, I did not: though Lord F—, who hates his wife, was evidently much struck with me. He asked me to dance with him twice—he is a charming dancer, by-the-by, and so am I: you can’t think how well I did—I was astonished at myself. My lord was very complimentary too—rather too much so in fact—and I thought proper to be a little haughty and repellent; but I had the pleasure of seeing his nasty, cross wife ready to perish with spite and vexation—’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 55).

▪ Matilda Murray:

She was two years younger than Rosalie and, unlike this one, she was considerably less attractive. Dark-skinned, her features were more strong and her physical build was larger. Although she could not be considered an ugly girl, her father’s influence had made her extremely careless not only in her physical appearance, but also in her manners. Matilda herself had gotten into the habit of constantly swearing whenever she felt frustrated, which often happened as she didn’t have the patience to finish any task she was given to do. Her temperament, moreover, was violent and indomitable like that of a beast. She was not interested in bringing out her feminine side, or indulging in the same hobbies as her sister or her mother. Instead, she enjoyed horseback riding; playing with the dogs; socialize with her father and the rangers during the hunting season, since she was not allowed to participate in said activity; and getting into mischief with her brothers John and Charles.

‘Now, Miss Grey,’ exclaimed Miss Murray, immediately I entered the schoolroom, after having taken off my outdoor garments, upon returning from my four weeks’ recreation, ‘Now—shut the door, and sit down, and I’ll tell you all about the ball.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 53).

‘No—damn it, no!’ shouted Miss Matilda. ‘Hold your tongue, can’t ye? and let me tell her about my new mare—such a splendour, Miss Grey! a fine blood mare—’

‘Do be quiet, Matilda; and let me tell my news first.’

‘No, no, Rosalie; you’ll be such a damned long time over it—she shall hear me first—I’ll be hanged if she doesn’t!’

▪ John Murray:

At the time of Miss Grey’s arrival at Horton Lodge, the boy was already eleven years old. He was a kind-hearted and noble-minded creature. However, he had not been taught to control his impulses so he was an undisciplined and restless child. His mother spoiled him excessively, as she did also with little Charles. The degree of his ignorance in the three R’s was such that he barely met the requirements to be admitted to any boarding school as a student. Still, he entered one of these institutions to be provided with proper education, since home schooling had not given any results.

▪ Charles Murray:

He was Mrs. Murray’s favorite son. Despite being only a year younger than his brother John, his physical build was much more frail and small-boned. He was a moody, capricious, fearful and selfish little boy. He practically couldn’t read, let alone he was able to solve simple arithmetic problems. His mother insisted that all those tasks that were too difficult for him should be carried out by his governess, thus avoiding any type of frustration for the childe. Due to Mrs. Murray’s pedagogy as to how the boy should be brought up, Charles would respond furiously if he was required to exercise his mental faculties as he was to make no effort to cultivate his intellect. Charles was sent to the same boarding school as his brother after two years of unsuccessful attempts by Miss Grey to instill a few basics in him.

Farmers

▪ Nancy Brown:

In a humble dwelling, within the grounds of Horton Lodge, and thus owned by Mr. Murray, lived a young man who worked long hours as a day laborer in the fields, and his mother, an elderly woman with various medical conditions. Nancy Brown, who suffered from an eye disease that prevented her from reading, was regularly visited by Miss Gray and Mr. Weston, who offered themselves to read passages from the Bible to the pious woman. Fearing the wrath of God, Master Hatfield’s words often plunged her into the deepest anguish. Putting aside the worries to which she gave herself due to this state of anxiety, she was a selfless old woman who tried to help her neighbors by sewing and weaving sucks, scarves, etc.

And I am happy now, thank God! an’ I take a pleasure, now, in doing little bits o’ jobs for my neighbours—such as a poor old body ’at’s half blind can do; and they take it kindly of me, just as he said. You see, Miss, I’m knitting a pair o’ stockings now;—they’re for Thomas Jackson: he’s a queerish old body, an’ we’ve had many a bout at threaping, one anent t’other; an’ at times we’ve differed sorely. So I thought I couldn’t do better nor knit him a pair o’ warm stockings; an’ I’ve felt to like him a deal better, poor old man, sin’ I began. It’s turned out just as Maister Weston said.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 68).

▪ Mark Wood:

Their home was also within the grounds surrounding the splendid Murray’s mansion. Mark was a gravely ill middle-aged factory worker that would soon be dead, leaving his unfortunate wife and children to their fate. Mr. Weston used to visit the laborer, easing his suffering with the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick. The priest also eased the grief of the sick man’s relatives with his religious speeches. Miss Grey did the same when her students allowed her a few hours to herself.

Clerics

▪ Mr. Hatfield:

Although his sermons were often tedious and solemn, his attitude as Rector of the parish was inconsistent with his sayings. Furthermore, his greed was such that led him to rub shoulders with the wealthy parishioners of the congregation, despite not belonging to their social stratum, and to woo women whose fortune could increase his. As the arrogant and contemptuous man that he was, he took pleasure in humiliating the most needy by publicly mocking their shortcomings and their sins. To conclude, he did not tolerate his authority as a clergyman being questioned, which is why he engaged in bitter discussions with anyone who dared to question his behavior or to act in a different way from the one imposed by him.

“Oh, it’s all stuff! You’ve been among the Methodists, my good woman.” But I telled him I’d never been near the Methodies. And then he said,—“Well,” says he, “you must come to church, where you’ll hear the Scriptures properly explained, instead of sitting poring over your Bible at home.”(…) “It’ll do your rheumatiz good to hobble to church: there’s nothing like exercise for the rheumatiz. You can walk about the house well enough; why can’t you walk to church? The fact is,” says he, “you’re getting too fond of your ease. It’s always easy to find excuses for shirking one’s duty.”(…) “The church,” says he, “is the place appointed by God for His worship. It’s your duty to go there as often as you can. If you want comfort, you must seek it in the path of duty,”(…) “But if you get no comfort that way,” says he, “it’s all up.” (…) “Why,” says he—he says, “if you do your best to get to heaven and can’t manage it, you must be one of those that seek to enter in at the strait gate and shall not be able.”

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 64 and 65).

▪ Mr. Weston:

As the elderly Mr. Bligh retired from his post as curate, Mr. Weston became Mr. Hatfield’s new assistant. With a serene and cheerful personality, he also had a natural predisposition to give himself to others. His comments and observations on any topic were brief and concise, showing the clarity of his ideas. However, this meant that he was somewhat abrupt in the way he expressed himself, since he did not care about the rules of etiquette regarding how a gentleman should behave in society. In addition to serving God, having lost his mother a few months ago, he fervently longed to have his own household.

What kind of people are those ladies—the Misses Green?’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 92 and 93).

‘I really don’t know (…) I never exchanged a word with either of them.’

‘Indeed? They don’t strike me as being particularly reserved.’

‘Very likely they are not so to people of their own class; but they consider themselves as moving in quite a different sphere from me!’

He made no reply to this: but after a short pause, he said,—‘I suppose it’s these things, Miss Grey, that make you think you could not live without a home?’(…) Are you so unsociable that you cannot make friends?’

‘No, but I never made one yet; and in my present position there is no possibility of doing so, or even of forming a common acquaintance. The fault may be partly in myself, but I hope not altogether.’

‘The fault is partly in society, and partly, I should think, in your immediate neighbours: and partly, too, in yourself; for many ladies, in your position, would make themselves be noticed and accounted of.

Grey family

▪ Richard Grey:

As a young man he fell in love with a lady belonging to the highest echelon of society. He had the blessing that the said woman corresponded to his feelings, and agreed to become his wife. Mr. Grey’s happiness did not diminish when the family of his fiancée decided to disinherit his lovely bride as a sign of opposition to their forthcoming wedding. Yet, as the years went by, Mr. Grey began to tortured himself by recalling the comfortable position of which he had deprived his wife. He was also concerned about his meager savings as a clergyman that would not allow him to leave a dowry to her two young daughters. With the intention of providing his family with a better income, he invested his capital in a commercial enterprise that ended up bringing about his ruin. Sinking into a deep depression, his health seriously deteriorated. Richard Grey thus resigned himself to spending the rest of his days afflicted by guilt and remorse. Although the debts incurred were settled after a few years, his physical conditions worsened and ended his life.

‘Oh, Richard!’ exclaimed she, on one occasion, ‘if you would but dismiss such gloomy subjects from your mind, you would live as long as any of us; at least you would live to see the girls married, and yourself a happy grandfather, with a canty old dame for your companion.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 36 and 37).

My mother laughed, and so did my father: but his laugh soon perished in a dreary sigh.

‘They married—poor penniless things!’ said he; ‘who will take them I wonder!’

‘Why, nobody shall that isn’t thankful for them. Wasn’t I penniless when you took me? and you pretended, at least, to be vastly pleased with your acquisition. But it’s no matter whether they get married or not: we can devise a thousand honest ways of making a livelihood. And I wonder, Richard, you can think of bothering your head about our poverty in case of your death; as if that would be anything compared with the calamity of losing you—an affliction that you well know would swallow up all others, and which you ought to do your utmost to preserve us from: and there is nothing like a cheerful mind for keeping the body in health.’

‘I know, Alice, it is wrong to keep repining as I do, but I cannot help it: you must bear with me.’

‘I won’t bear with you, if I can alter you,’ replied my mother: but the harshness of her words was undone by the earnest affection of her tone and pleasant smile, that made my father smile again, less sadly and less transiently than was his wont.

▪ Mrs. Grey:

Alice’s father gave his consent for her daughter’s wedding to take place, making it clear to the young lady that she would be giving up the family fortune if she insisted in her decision to unite her life with Richard Grey’s. The priest’s fiancée, without thinking twice, agreed to such conditions. After becoming Mrs. Grey, she pretty much lost contact with her relatives.

Alice was a faithful and affectionate mother and wife. She committed herself to educating her daughters, and nursed her husband during his illness. As in her youth, she was a perky, punctilious, and tireless woman with a great sense of humor. These personality traits allowed her to cope with the tough time of her marriage, and to overcome the death of several of her children. For the same reason, she refused to receive help from others while trying, in turn, to be attentive to the needs of others.

‘No, Mary,’ said she, ‘if Richardson and you have anything to spare, you must lay it aside for your family; and Agnes and I must gather honey for ourselves. Thanks to my having had daughters to educate, I have not forgotten my accomplishments. God willing, I will check this vain repining,’ she said, while the tears coursed one another down her cheeks in spite of her efforts; but she wiped them away, and resolutely shaking back her head, continued, ‘I will exert myself, and look out for a small house, commodiously situated in some populous but healthy district, where we will take a few young ladies to board and educate—if we can get them—and as many day pupils as will come, or as we can manage to instruct.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 112 and 113).

▪ Mary Grey:

As the eldest daughter, she was still single at the age of twenty-five, which was considered unusual at the time. However, let us remember that Mr. and Mrs. Grey did not have the economic resources to formally present their daughters in society, and, likewise, the two girls had to work alongside their parents in order to have the basic sustenance to live with dignity and not fall into poverty. Thus, it was not uncommon for daughters of low-income families to marry at a later age than those belonging to the upper class, or to the aristocracy, since they had fewer opportunities to meet potential suitors. Furthermore, the small dowry that their parents could provide in the event of an engagement was another matter to be considered by any man who intended to marry them.

Mary was a hardworking and humble young woman. She had a great talent for painting, by which she managed to obtain a regular remuneration by selling her artistic production. Being almost six years older than Agnes, she gave herself less to the illusions and fantasies of youth, being more reality-focused in her way of thinking. Still, this didn’t stop her from being attached to her family. Great sorrow experienced the unfortunate Mary when her sister decided to become a governess and moved several miles away from their home. In relation to the above, she always behaved in a somewhat maternal way with Agnes, considering the little girl as if she were a candid and defenseless creature. Therefore, she tried to avoid any concern or discomfort to her dear sister.

▪ Agnes Grey:

The protagonist of the story was a withdrawn, shy and insecure young woman who frequently doubted her own worth as a person. Despite her efforts, she encountered several difficulties in working as a governess. Partly for this reason, her disappointments were more than the gratifications obtained in said activity.

As a consequence of the education received at home, Agnes governed her life by the precepts of Anglicanism. Therefore, she tried to instill these teachings in her students. Furthermore, she led by example dedicating her leisure time to helping those most in need.

In the first chapters of the novel, Agnes is shown to be too susceptible to the criticism of her masters. As the story progresses, the girl manages to overcome her fears by correcting some of her personality flaws, though her employer’s comments continue to affect her to some extent.

Amid all this, let it not be imagined that I escaped without many a reprimand, and many an implied reproach, that lost none of its sting from not being openly worded; but rather wounded the more deeply, because, from that very reason, it seemed to preclude self-defence. Frequently, I was told to amuse Miss Matilda with other things, and to remind her of her mother’s precepts and prohibitions. I did so to the best of my power: but she would not be amused against her will, and could not against her taste; and though I went beyond mere reminding, such gentle remonstrances as I could use were utterly ineffectual.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 107).

Locations

The different scenarios described by the author reflect the idiosyncrasy of a social class made up of individuals from different economic contexts. On the one hand, the merchants who knew how to make a fortune; on the other, the rural nobility; and finally, the aristocracy.

In “Agnes Grey”, the descriptions of the halls, the rooms, and other enclosures, are brief and with few details. However, the greatness of one and others is deduced from the dialogues between owners and heirs when referring to their social status, and by observing the behavior of each of these characters when relating to other wealthy families. Thus, the Bloomfields’ abode, as well as the Murray’s home, represents the wealth they possess. In the case of the Grey’s house, it symbolizes the lack of comfort with which they live even as a middle-class family. Something similar happens with Nancy Brown’s modest cabin, as this old woman finds herself plunged into poverty.

That said, the countryside, townscape, manor houses, and cottages where the plot takes place are mentioned below.

A. Wellwood House:

It was an elegant and high-ceilinged residence, surrounded by two parks with plantations of young trees. Next to the house, there was a beautiful garden with a prodigious variety of flowers, arranged with great care and delicacy. Between the edge of the garden and one of the nearest parks, there was a pothole with water in which the children used to splash, dirtying their clothes. Wellwood House’s lands also extended over fields where hunting was possible.

B. Horton Lodge:

As the very old mansion that it was, it had a costly and luxurious parlour, an splendid ballroom, and opulent bedrooms. A few meters from the house, an immense park with ancient trees and deer walking around could be seeing. A field stretched beyond it’s limits; this one with wide paths, diversity of plant species, and more trees here and there. Only the flatness of the land could be pointed out as an unattractive feature of the landscape.

C. Unknown county; possible Yorkshire (hometown of the protagonist):

Heathers, primroses and bluebells graced this setting of rugged hills. The Grey family resided in a humble dwelling belonging to the municipality’s parish. A small garden with a willow tree was the only adjoining ground to walk during leisure hours. No other information is provided regarding this village.

D. A– (Spa city):

There was a path that led to the coast. Tourist liked to walk along it until they reach the sandy area, where there was a“semicircular barrier of craggy cliffs surmounted by green swelling hill” and “low rocks out at sea—looking, with their clothing of weeds and moss, like little grass-grown islands”(page 132). Gulfs and lakes also bordered the foamy shore.

In the vicinity of the city center, in the northwest, there was “a row ofrespectable-looking houses, on each side of the broad, white road, with narrow slips of garden-ground before them, Venetian blinds to the windows, and a flight of steps leading to each trim, brass-handled door” (page 131).

E. Ashby Park:

The mansion bore several similarities to Horton Lodge. In the first place, it was as old as this one. Secondly, it had a beautiful park with centuries-old trees, and herds of deer that walked through them. It also had a beautiful lake where these animals quenched their thirst.

Ideas and Concepts expound

1) The hypocrisy of the Clergy:

In the 19th century, it was still common for young men, to choose to earn a living as priests, probably because they had no other opportunity to make a fortune. Their duties were quite simple: preach the word of God, teach the plebs how to interpret the Holy Scriptures, conduct religious ceremonies, and listen to the confessions of the parishioners. Of course, since their motivation was to find a placement that would provide them with an increasing income, they exercised their functions in an authoritarian manner and according to their own interests. The welfare of the faithful was far from being one of their concerns. The middle and lower classes were the only ones who suffered the consequences of this dishonest behavior, since the upper class and the aristocracy maintained a close relationship with the Anglican Church.

In “Agnes Grey”, the character of Hatfield, with his haughtiness and grandiloquence, brings out this issue on several occasions:

- In chapter n⁰10, the clergyman gives a sermon after which he boasts of his words with the Melthams and the Greens (some of the wealthy families in the area) mocking some of the poorest peasants of the parish’s community as Betty Holmes, George Higgins and Thomas Jackson.

- In chapter n⁰11, Nancy Brown approaches him, worried about the salvation of her soul, and the parson ignores her pleas and dismisses her with brusqueness and disdain. He even goes so far as to refer to the woman as an“hypocrite”.

- In chapter n⁰9, Rosalie Murray praises his pomposity, in contrast to the manners and behavior of Mr. Weston, who wears a silver watch, instead of a gold one, and less colorful clothes than the Rector of the parish.

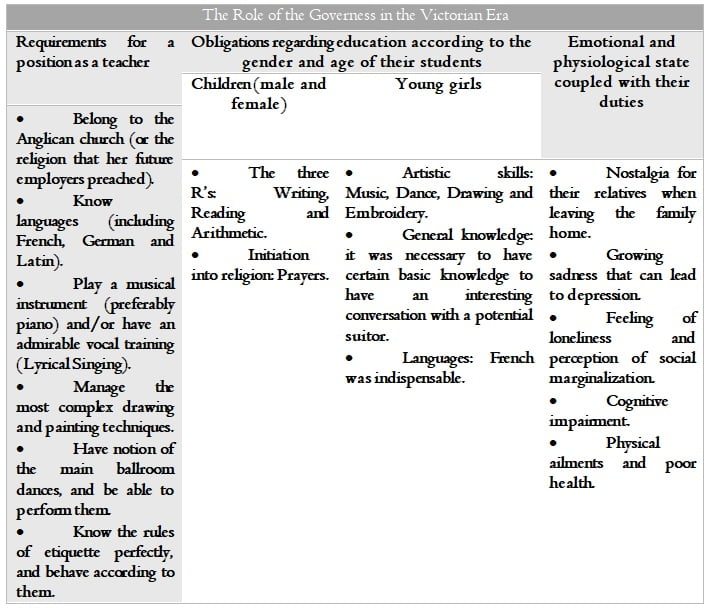

2) The Role of Governesses during the reign of Queen Victoria:

The story faithfully portrays the conditions in which governess had to live in Victorian Era. To begin with, the women who worked as governesses were disgraced middle-class ladies, so they offered their services as teachers to upper-class families looking for a tutor to take charge of their children’s education. The governesses had under their tutelage both boys and young ladies. In the case of boys, they remained under the wing of their governess until they reached the age of twelve years old, when they were often sent to boarding school. The situation was quite different with regard to girls, as it was not customary to send them to an institution to provide them of a proper education. The daughters of wealthy marriages were educated at home. The role of the governess, in this sense, changed according to the age of her female students. When they were little kids, she taught them to read and write. When they entered puberty, instead, she had to teach them languages, drawing, painting, dance and music, since their first formal appearance in society would take place at the age of eighteen. The governess also had to instill in the young ladies the rules of etiquette by which society was governed. We share a quote from Miss Grey:

For the girls she seemed anxious only to render them as superficially attractive and showily accomplished as they could possibly be made, without present trouble or discomfort to themselves; and I was to act accordingly—to study and strive to amuse and oblige, instruct, refine, and polish, with the least possible exertion on their part, and no exercise of authority on mine.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 44).

Before being hired, governesses had to meet certain requirements. Extensive knowledge of different subjects and disciplines was expected of them; a certain elegance in their walk; delicacy in their dealings with others; and a Christian resignation to fulfill the responsibilities that would be required of them. On the other hand, it should be mentioned that the students often became fond of their teacher as they spent more hours with her than with their parents. Therefore, it was not surprising that the latter expected a maternal behavior from the governess; though it must be said that she could not exercise any kind of authority over the children. Mrs. Murray refers to this particular when receiving Miss Grey at Horton Lodge:

… I hope you will keep your temper, and be mild and patient throughout (…) You will excuse my naming these things to you; for the fact is, I have hitherto found all the governesses, even the very best of them, faulty in this particular (…) But I have no doubt you will give satisfaction in this respect as well as the rest. And remember, on all occasions, when any of the young people do anything improper, if persuasion and gentle remonstrance will not do, let one of the others come and tell me; for I can speak to them more plainly than it would be proper for you to do. And make them as happy as you can, Miss Grey, and I dare say you will do very well.’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 44).

The salary of governesses used to be very low. Some even did not receive any type of remuneration at all; they had to be satisfied with the lodging provided to them in their masters’ houses. On the other hand, those who were lucky enough to get a position within a respectable family, were not treated kindly by the people they interacted on a daily basis. In the 19th century, the need for a woman from a good family to work was considered a demeaning situation. For this reason, the governesses were subject to frequent humiliation both by their employers and by the servants.

To these tortures were added still others. Social isolation was one of them. Despite being most of the time with ladies and gentlemen of a higher stratum, the governesses did not even have occasion to exchange a few words with them. The governess was not considered a member of the family, nor part of the domestic service. Therefore, her condition as a teacher deprived her of being able to establish friendships, or any other type of affective bond, with those who, in other circumstances, would have been considered her equals due to their socio-educational level, or with those who belonged to her current social class because of their income (ie, maids, gardeners, drivers, etc.). Anne Brontë expresses this situation through the thoughts of the protagonist of the novel:

Never, from month to month, from year to year, except during my brief intervals of rest at home, did I see one creature to whom I could open my heart, or freely speak my thoughts with any hope of sympathy, or even comprehension: never one, unless it were poor Nancy Brown, with whom I could enjoy a single moment of real social intercourse, or whose conversation was calculated to render me better, wiser, or happier than before; or who, as far as I could see, could be greatly benefited by mine. My only companions had been unamiable children, and ignorant, wrong-headed girls; from whose fatiguing folly, unbroken solitude was often a relief most earnestly desired and dearly prized.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 70).

Another of the sufferings that a governess had to go through was intellectual stagnation. Submitted for long hours to the care of children and young girls, the time she had left for herself was so scarce that she could hardly use it to reading or to any other activity that stimulated her senses. Thus, she only devote herself to the lessons she imparted day after day to her students. Again, we share a quote from Miss Grey to illustrate what has just been described:

Never a new idea or stirring thought came to me from without; and such as rose within me were, for the most part, miserably crushed at once, or doomed to sicken or fade away, because they could not see the light.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 70).

Considering what we have exposed, and in consonance with the quotes of the novel, the following table intends to detail the different tasks that a governess had to carry out, and mention the emotional exhaustion to which she was subjected.

Criticism

Anne Brontë’s work has several inconsistencies that act to the detriment of the narrative quality of the story.

I. A failed plot:

The first paragraph of the story promises the reader intrigues, conflicts and scandals. However, this illusion vanishes in chapters one to five. These are the words of the protagonist that arouse expectations that never come true:

Shielded by my own obscurity, and by the lapse of years, and a few fictitious names, I do not fear to venture; and will candidly lay before the public what I would not disclose to the most intimate friend.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 2).

Leaving aside the humiliations and insults to which Miss Grey is subjected, the narration is not characterized by particularly embarrassing situations that justify such a mystery atmosphere with the excuse of protecting the identity of those who suffer from them. On the other hand, the argument itself is practically unsubstantial. As the chapters follow each other, there are few events that generate interest and encourage the reader to go on reading. Furthermore, once these events are introduced in the novel, the author quickly neglects them without developing the subplots they open.

II. Hatfield’s threat to Rosalie Murray; the entanglement wasted by Anne Brontë:

When in chapter nº14 Hatfield declares his love to Rosalie, she rejects him with cruelty and disdain despite being romantically interested in the priest. Hurt in his feelings, and in his pride, after his beloved’s refusal, Hatfield begs Miss Murray not to tell anyone what happened between them. However, the plea soon turns into a warning. Hatfield, suspecting that Rosalie has seduced him for the sole purpose of humiliating him, makes it clear that he intends to destroy the young lady’s reputation if she does not comply with his request.

Of course, Rosalie accepts the conditions imposed by the Clergyman to prevent the matter from going any further. Even so, as soon as the interview between them ends, the girl begins to tell what happened to her governess, her sister, and then to her mother, breaking the promise made.

Interestingly, the conflict between the two characters concludes here. Hatfield never finds out about Rosalie’s betrayal, and the young woman, meanwhile, is lucky enough that none of her relatives spread the incident among the landed gentry in the area.

This is one of the most significant events of the novel, and unfortunately also one of the most disregarded by the writer as such. The episode had two possible outcomes; the one that actually takes place in the book, or one involving defamations and a ruthless revenge on Hatfield’s behalf. Although the author has opted for the first of these two options, it’s elaboration is practically null, since the incident is barely mentioned again. Thus, one of the most interesting subplots of the story is completely throw away.

III. Rosalie Murray’s obsession with Edward Weston; a fake love triangle:

After her unsuccessful relationship with Maese Hatfield ends, Rosalie is determined to win his assistant’s heart to make up for the loss of the most ardent admirer she’s ever had. Aware of the attraction between Edward Weston and Miss Grey, Miss Murray manages to prevent any chance encounters between them. Meanwhile, in complicity with her sister, she arranges brief interviews with the curate to display all her charms and bring him closer to her.

Edward Weston, at first, seems to feel affection for the young woman, and to have a preference for her companionship. At a critical point in the story, even Miss Grey considers it possible that the priest ends up falling in love with Rosalie. However, this does not happen.

The state of affairs introduces two possible outgrowths just like the case we have analyzed in the previous section. The first is, as we have already implied, that Mr. Weston falls in love with Miss Murray. The second, on the other hand, portrays Rosalie’s defeat. The writer, paradoxically, has not opted for either of them.

Although Edward Weston does not become romantically involved with the lady, and she fails to carry out her plans, said woman is far from feeling the frustration of her failure. Rosalie continues with the plans that her mother has for her, and ends up forgetting about Mr. Weston without much regret on her part when thinking about the matter. In a sense, it could be said that Rosalie is never aware that her efforts have been in vain; simply, as the novel progresses, her life takes a different course from Mr. Weston’s, and she loses touch with him.

Rosalie’s frivolity admits this outcome as a third option; but it is not consistent with the facts and circumstances that are intertwined with the love conflict between the characters involved in this situation.

IV. Narrative structure inconsistent with the protagonist’s sayings in this regard:

In the last lines of the book, the heroine states that the story she has written is a compilation of pages from a private diary that she has carried with her for years. This revelation implies a contradiction, since the narration offers a perspective on the events that only the passage of time can give. In other words, the events are not reported in the immediate past. On the other hand, in the first paragraph of chapter n⁰1, Miss Grey alludes to her intentions of sharing with the readers the most intimate secrets of her youth, as she is now a middle-aged woman. For this reason, the protagonist’s comments in the last chapter exhibit the little skill of the author in the literary matters.

Similarities with the work of Jane Austen

Although there is no reliable information on the influence that Austen may or may not have exercised posthumously on Anne Brontë, since it is not even known with certainty if the latter dedicated herself to the study of her predecessor’s work, “Agnes Grey” show more than one similitude to Austen’s novels.

1) Genre: Realism and Costumbrismo

Although both artistic movements are considered typical of the 19th century, the literary production of some 18th century writers was also framed within these two styles. Jane Austen is an example of this.

It must be said, first of all, as far as Literary Realism is concerned, that Austen’s narrative is characterized by a technique that is far from that of other representatives of this artistic movement. Austen does not usually provide a detailed description of the landscapes, or the physical appearance of the characters. However, this does not mean that they do not play an important role in her novels. Jane Austen highlights the characteristics of the different scenarios by procedures other than the usual ones, such as some specific observations on her part, or isolated comments on behalf of the individuals who interact with each other in the story. The same happens with this or that physical or psychological peculiarity of the protagonists. However, it should be noted that Austen’s works are considered “realistic”, more than anything, for portraying the activities in which the different members of English society were involved at that time. This, in turn, has positioned her as a “costumbrista” writer.

Anne Brontë, perhaps without knowing it, elaborates her novel following in the footsteps of Jane. However, there is a difference between the two writers. Anne Brontë portrays certain scenes with greater precision, thus revealing some of the most ruthless and brutal practices of human beings in the middle of the Victorian Era. The incidents concerning Tom Bloomfield, and his pleasure in animal abuse, described in “Agnes Grey“, are proof enough of this.

In a final approach to the work of these authors, the style of Anne Brontë in “Agnes Grey” corresponds, above all, to Literary Realism, and secondarily to Literary Costumbrismo. In the case of Jane Austen, all of her novels are part of the costumbrista genre, and in a second instance they are also considered typical of Realism.

2) Writing techniques

a) Breaking the Fourth Wall:

The “Fourth Wall” is a concept that emerged in the second half of the 18th century to refer to an implicit practice in the performing arts, by which it is assumed that there is a wall between the public and the actors who are on stage. This imaginary wall prevents the actors from seeing their audience, while allowing the latter to contemplate the performance.

When speaking of “breaking down” the “fourth wall”, reference is made to an action that diverts audience’s attention, making them suddenly aware of the time and space in which the action takes place, reminding them that what they are looking at is a mere fantasy. This is usually accomplished by interrupting the narrative discourse by having one of the characters address the audience trying to engage with them through dialogue. In literary works that do not require staging, one proceeds in the same way; that is, introducing a soliloquy by the protagonist or the author himself in an attempt to strike up a conversation with the reader.

Both Jane Austen and Anne Brontë use this resource frequently. Austen’s work is well known for being characterized by the use of this technique. In the case of Anne Brontë, this procedure is more subtle and less disruptive, since in “Agnes Grey”, the narrator is also the protagonist. This brings with it the decision to write the story using direct speech (which makes it possible to “break the four wall”), in addition to indirect speech on certain occasions.

b) Irony and Sarcasm:

Although these terms can sometimes be confused with each other, irony and sarcasm are different concepts. Irony is affirming the opposite of what is meant, while sarcasm is a true statement about a particular situation expressed in a biting and witty way.

Austen uses both devices to add a touch of comedy to her novels and criticize the English society of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Anne Brontë, for her part, is more measured in the use of one and the other. Still, she proceeds in the same way as Jane Austen. When Mrs. Murray addresses to Miss Grey for the umpteenth time to ask her to correct Matilda’s bad habits, she expresses herself as follows:

‘Dear Miss Grey! it is the strangest thing. I suppose you can’t help it, if it’s not in your nature—but I wonder you can’t win the confidence of that girl, and make your society at least as agreeable to her as that of Robert or Joseph!’

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial; page 107).

Shortly after, in the same conversation, Mrs. Murray goes on to say:

When we wish to decide upon the merits of a governess, we naturally look at the young ladies she professes to have educated, and judge accordingly. The judicious governess knows this: she knows that, while she lives in obscurity herself, her pupils’ virtues and defects will be open to every eye; and that, unless she loses sight of herself in their cultivation, she need not hope for success.

(Agnes Grey, written by Anne Brontë; Free Editorial Losada; page 108).

The first quote is an example of Sarcasm, since Mrs. Murray wishes to convey exactly the same idea that she has expressed verbally. The second quote, on the other hand, is an example of Indirect Irony. Ms. Murray, in this case, does not explicitly refer to Ms. Grey’s performance. However, by saying “The judicious governess knows this”, she is implying that the aforementioned is far from being sensible in her behavior. Jane Austen’s works, such as “Emma” or “Pride and Prejudice”, show this type of irony in a number of passages. It’s precisely this figure of speech that characterizes Austen’s style and makes her one of the most complex authors to analyze.

Personal Life and Fiction

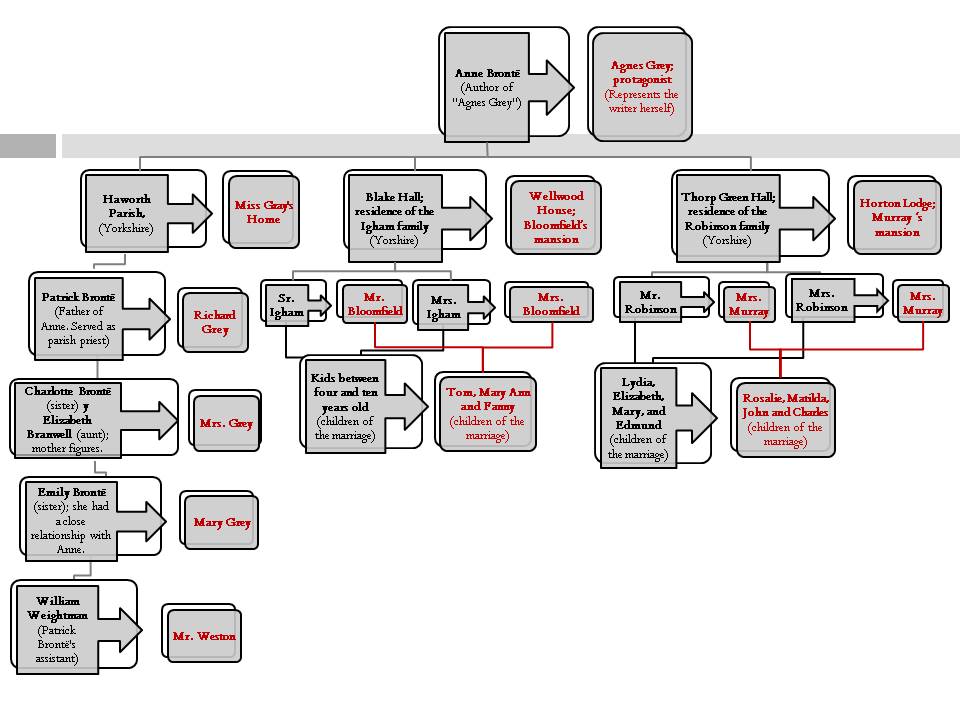

Anne Brontë’s novel is based on her experiences as a governess, and some facts concerning her family.

To begin with, Anne was the daughter of a parson. She was the youngest of six children, of whom two girls died in a boarding school. Due to this unfortunate incident, she and her two other sisters, Charlotte and Emily, and the family’s only son, Patrick, were homeschooled. Her father and her maternal aunt took it upon themselves to properly educate the four children (their mother had died shortly after giving birth to Anne).

At the age of fifteen, Anne entered a school where her elder sister, Charlotte, worked as a teacher. In that institute Anne completed her education. Four years later, in 1839, Anne was hired as a governess by the Ingham, owners of the Blake Hall mansion. The experience was extremely traumatic for Anne. The children were unruly, and their parents were disrespectful and contemptuous. Anne was fired after eight months.

On her return to the her home, Anne met a handsome and courteous young man named William Weightman, whom her father had hired as an assistant. Anne is believed to have fallen in love with said gentleman. Unfortunately, the twenty-five-year-old priest died of cholera in 1842.

Shortly after her return to the parish, Anne secured another position as governess. On this occasion, she was hired by the Robinson to take charge of the education of three girls and one boy. Therefore, Anne took up residence at Thorp Green Hall, the lovely country house of her employers. She lived there for nearly six years, from 1840 to 1846. Despite receiving better treatment from Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, as well as from her pupils, Anne suffered from frequent bouts of melancholy. After resigning as a teacher, she returned once more to her house where she devoted herself, along with her sisters, to writing and looking for publishers for her short stories and poems.

Conclusion

Although some scholars consider “Agnes Grey” as a transcendental work in the history of universal literature, it is more of an outline of a possible compelling plot than a novel in itself. The constant blunders in which the author incurs, together with the poverty of vocabulary, explain the negative criticism it received after its publication in 1847. It is likely that Anne Brontë decided to publish her work without stopping to consider its quality, driven by the economic needs of her family. Even so, “Agnes Grey” is an interesting testimony about the sufferings of governesses in the middle of the 19th century.

Bibliography

-ABC Education. Jane Austen: The novel and social realism. Recuperado de https://www.abc.net.au/education/jane-austen-the-novel-and-social-realism/13947526

-British Library. Gender roles in the 19th. Recuperado de https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gender-roles-in-the-19th-century

-British Library. Jane Austen: social realism and the novel. Recuperado de https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/jane-austens-social-realism-and-the-novel#:~:text=Jane%20Austen%27s%20social%20realism%20includes,financial%20security%20and%20social%20respect.

-Cove Editions. The Rol of the Governess in Victorian Society. Recuperado de https://editions.covecollective.org/blog/role-governess-victorian-society

-English History. Anne Brontë. Recuperado de https://englishhistory.net/poets/anne-bronte/

-Mimi Matthews. The Vulnerable Victorian Governess. Recuperado de https://www.mimimatthews.com/2018/02/12/the-vulnerable-victorian-governess/

-The Guardián. Anne Brontë: the sister who got there first. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jan/06/anne-bronte-agnes-grey-jane-eyre-charlotte

-The History Press. Literary legends: Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters. Recuperado de https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/literary-legends-jane-austen-and-the-bront%C3%AB-sisters/

-Slate. Between upstairs and downstairs. Recuperado de https://slate.com/culture/2016/03/jane-eyre-and-the-precarious-status-of-the-victorian-governess.html

-Stanford News. Stanford literary scholars reflect on Jane Austen’s legacy. Recuperado de https://news.stanford.edu/2017/07/27/stanford-literary-scholars-reflect-jane-austens-legacy/

-Victorians TTU. The Governess in Jane Eyre. Recuperado de https://victoriansttu.wordpress.com/the-governess/